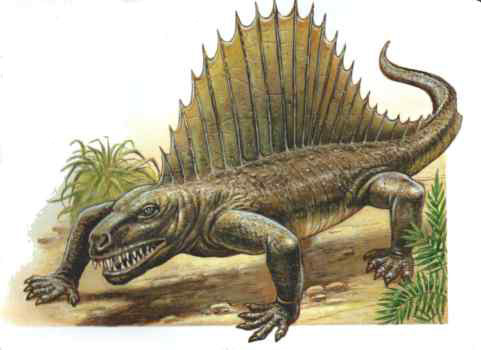

Ecosystem Remodelling Among Vertebrates During The Permian-Triassic Extinction

ScienceDaily (Nov. 9, 2004) — The biggest mass extinction of all time happened 251 million years ago, at the Permian-Triassic boundary. Virtually all of life was wiped out, but the pattern of how life was killed off on land has been mysterious until now. A team from Bristol University and Saratov University, Russia, have now laid the evidence bare.

The Bristol and Russian researchers have documented the event in Russia after looking at 675 specimens of amphibians and reptiles from 289 areas spanning 13 successive geological time zones in the South Urals basin. The study will be reported in Nature Thursday, November 4.

The mass extinction at the Permian-Triassic boundary is accepted as the most profound loss of life on record. Records indicate a loss of 50 per cent of animal groups or more, in both sea and on land, with a loss of 80 to 96 per cent of species. Local and regional-scale studies of marine specimen confirm the loss, but the terrestrial record has been harder to analyse in such close detail.

There was a profound loss of animal groups, and simplification of ecosystems, with the loss of small fish eaters and insect eaters, medium and large herbivores and large carnivores. Plant life also changed, from high rates of turnover through the Late Permian period to greater stability at low diversity through the Early Triassic period. Even after 15 million years of ecosystem rebuilding, some groups were still absent—small fish eaters, small insect eaters, large herbivores and top carnivores.

The end-Permian mass extinction is now thought to have been caused by gigantic volcanic eruptions, which triggered a runaway greenhouse effect and nearly put an end to life on earth.

Mike Benton, Professor of Vertebrate Palaeontology and Head of the Department of Earth Sciences at Bristol University, said: “At the end of the Permian there was a high turnover in animal families on land however these were largely destroyed by the Permian-Triassic extinction. However, after that the animal groups recovered slowly and diversity gradually increased.â€

Ecosystem remodelling among vertebrates at the Permian–Triassic boundary in Russia, M J Benton, Department of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol and V P Tverdokhlebov and M V Surkov, Geological Institute of Saratov State University, Russia. Nature, 4 November 2004.

Adapted from materials provided by University Of Bristol.

Prehistoric crocodiles

Scientists Unveil Prehistoric “Sea Warrior” Crocodile

A fossil of a new prehistoric crocodile species “Guarinisuchus munizi” is seen during a press conference at National Museum of the Rio de Janeiro Federal University in Rio de Janeiro, Wednesday, March 26, 2008. Brazilian scientists say they have found a new prehistoric crocodile species that inhabited the Earth’s oceans some 62 million years ago.

(Ricardo Moraes/AP Photo)Pointy-nosed crocodiles may have joined sharks as the dominant predators in the world’s oceans some 62 million years ago, according to Brazilian scientists who on Wednesday unveiled one of the most complete skeletons found yet of the prehistoric animals.

Scientists called it a new species, “Guarinisuchus munizi,” and said it sheds new light on the evolutionary history of modern crocodiles.

The fossil includes a skull, jaw bone and vertebrae, making it one of the most complete examples of marine crocodylomorphs collected so far in South America, said Alexander Kellner of the National Museum of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. He and other scientists unveiled fossils and a model of the 10-foot-long crocodile at the museum.

“It’s a very rare find and it gives rise to several new theories,” said Kellner, who co-authored an article on the find that was published Tuesday in Proceedings of The Royal Society B, a London-based peer-reviewed journal.

Guarinisuchus appears to be closely related to marine crocodylomorphs found in Africa, which supports the hypothesis that the group originated in Africa and migrated to South America before spreading into the waters off the North American coast, Kellner said.

The find also suggests that marine crocodylomorphs replaced marine lizards during the early Paleocene era, about 65 million years ago — the same time marine lizards became extinct. They believe it’s a new species based on anatomical differences in the skull that are unique to this creature.

Philip Currie, a paleontology professor at the University of Alberta, Canada who was not involved with the discovery, said it was an important find.

“There are a lot of unknowns with this group in terms of evolution. Clearly the discovery of a specimen as nice as this one will help sort things out,” Currie said in telephone interview.

The bones were found in the northeastern state of Pernambuco. Scientists named the species “Guarinisuchus” after the Tupi Indian word “Guarani,” which means warrior and “munizi,” in honor of Brazilian paleontologist Deraldo da Costa Barros Muniz, who has discovered many dinosaur fossils off Brazil’s northeastern coast. Muniz didn’t participate in this find.

Scientists have discovered a wealth of crocodile ancestors around Brazil in recent years.

In January, they announced the discovery of an 80 million-year-old land-bound reptile described as a possible link between prehistoric and modern-day crocodiles.

Two years ago, paleontologists from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro announced the discovery of a 70-million-year-old crocodile fossil that they called Uberabasuchus Terrificus, or “Terrible Crocodile of Uberaba.”

This “Terrible Crocodile of Uberaba” sounds interesting, so let’s dig up that story:

‘Terrible crocodile of Uberaba’ unveiled

Fossil offers look at Earth’s ecosystem of 70 million years ago

Thursday, February 17, 2005 Posted: 2109 GMT (0509 HKT)

RIO DE JANEIRO, Brazil (AP) — The discovery of a nearly intact fossil of a prehistoric crocodile is

teaching scientists what the world was like before the continents were separated by oceans, a Brazilian paleontologist said.

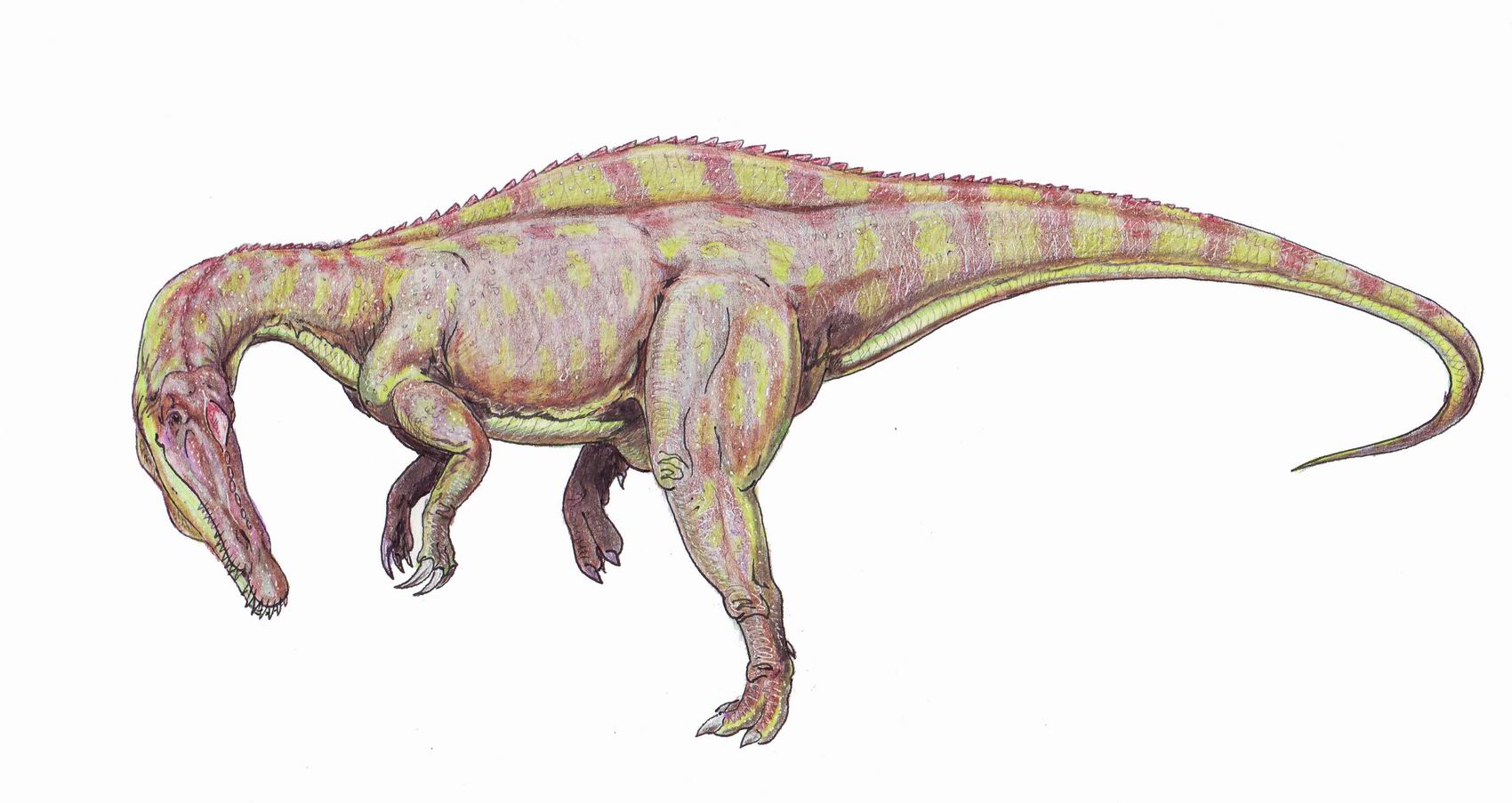

A reproduction of the previously unknown creature — dubbed Uberabasuchus terrificus, or the terrible crocodile of Uberaba, was unveiled Wednesday at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro.

Uberabasuchus lived 70 million years ago and was smaller than today’s crocodiles — only about three meters (10 feet) long and weighing about 300 kilograms (650 pounds), said paleontologist Ismar de Souza Carvalho.

“It’s important because the fossil was extremely well preserved, with 85 percent of its skeleton practically complete and intact,” he said.

Carvalho said Uberabasuchus lived on land — it was named because the fossil was found near Uberaba, an inland city in southeastern Brazil. It probably carried its body high off the ground on sturdy legs and was a strong and voracious hunter, he said.

“We’re learning about a new species of crocodile, the ecosystem of 70 million years ago, and the evolution of the land crocodile on the ancient continent of Gondwana,” Carvalho said.

Scientists believe the continents then were joined in a huge land mass, which some call Gondwana. Fossils similar to Uberabasuchus have been found in Africa and in Antarctica, which possibly were linked to South America.

Despite some similarities with modern-day crocodiles, Uberabasuchus became extinct when the other great dinosaurs died out, and it has no relation to today’s crocodiles, Carvalho said.

Brazil has drawn international attention for its recent discoveries of prehistoric creatures.

In December, scientists unveiled a replica of Unaysaurus tolentinoi, an ancestor of the huge Brontosaurus, that lived 230 million years ago in what is now southern Brazil. Experts said it was more closely related to fossils found in Germany than to dinosaurs from neighboring Argentina.

Zootaxa, a scientific journal published in New Zealand, said Unaysaurus “differs from all other dinosaurs.”

Carvalho predicted there was more to come.

“Important new discoveries are practically certain,” he said.

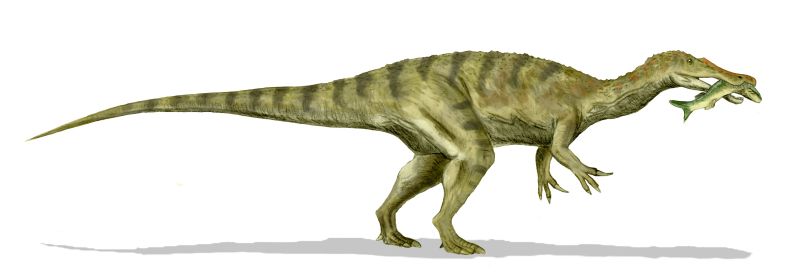

Crocodile-like Skull on fish eating dinosaur Baryonyx walkeri

Baryonyx walkeri was discovered in 1983. It has been dated to the Barremian period of Early Cretaceous Period, around 125 million years ago.

A rare example of a piscivorous (fish-eating) dinosaur with specialized adaptions like a long, narrow snout with lots of teeth

A similar dinosaur is Suchomimus tenerensis, who lived 110 to 120 million years ago, during the middle portion of the Cretaceous period in Africa.

Unusual Fish-eating Dinosaur Had Crocodile-like Skull

ScienceDaily (Jan. 14, 2008) — An unusual dinosaur has been shown to have a skull that functioned like a fish-eating crocodile, despite looking like a dinosaur. It also possessed two huge hand claws, perhaps used as grappling hooks to lift fish from the water.

Dr Emily Rayfield at the University of Bristol, UK, used computer modelling techniques — more commonly used to discover how a car bonnet buckles during a crash — to show that while Baryonyx was eating, its skull bent and stretched in the same way as the skull of the Indian fish-eating gharial — a crocodile with long, narrow jaws.

Dr Rayfield said: “On excavation, partially digested fish scales and teeth, and a dinosaur bone were found in the stomach region of the animal, demonstrating that at least some of the time this dinosaur ate fish. Moreover, it had a very unusual skull that looked part-dinosaur and part-crocodile, so we wanted to establish which it was more similar to, structurally and functionally — a dinosaur or a crocodile.

“We used an engineering technique called finite element analysis that reconstructs stress and strain in a structure when loaded. The Baryonyx skull bones were CT-scanned by a colleague at Ohio University, USA, and digitally reconstructed so we could view the internal anatomy of the skull. We then analysed digital models of the snouts of a Baryonyx, a theropod dinosaur, an alligator, and a fish-eating gharial, to see how each snout stressed during feeding. We then compared them to each other.”

The results showed that the eating behaviour of Baryonyx was markedly different from that of a typical meat-eating theropod dinosaur or an alligator, and most similar to the fish-eating gharial. Since the bulk of the gharial diet consists of fish, Rayfield’s study suggests that this was also the case for Baryonyx back in the Cretaceous.

Dr Angela Milner from the Natural History Museum, who first described the dinosaur and is co-author on the paper, said: “I thought originally it might be a fish-eater and Emily’s analysis, which was done at the Natural History Museum, has demonstrated that to be the case.

“The CT-data revealed that although Baryonyx and the gharial have independently evolved to feed in a similar manner, through quirks of their evolutionary history their skulls are shaped in a slightly different way in order to achieve the same function. This shows us that in some cases there is more than one evolutionary solution to the same problem.”

The unusual skull of Baryonyx is very elongate, with a curved or sinuous jaw margin as seen in large crocodiles and alligators. It also had stout conical teeth, rather than the blade-like serrated ones in meat-eating dinosaurs, and a striking bulbous jaw tip (or ‘nose’) that bore a rosette of teeth, more commonly seen today in slender-jawed fish eating crocodilians such as the Indian fish-eating gharial.

The dinosaur in question, Baryonyx walkeri, was discovered near Dorking in Surrey, UK in 1983 by an amateur collector, William Walker, and named after him in 1986 by Alan Charig and Angela Milner. It is an early Cretaceous dinosaur, around 125 million years old, and belongs to a family called spinosaurs.

Adapted from materials provided by University of Bristol, via EurekAlert!, a service of AAAS.