In search of suffocating sea squirt

By MARIAN GAIL BROWNArmed with sonar maps, cameras and a remote-controlled vehicle that looked ready for lunar exploration, University of Connecticut scientists plumbed the bottom of Long Island Sound on Tuesday for a slimy quarry.

The sea squirt, a blob-shaped animal with exponential reproductive powers, threatens to snuff out young lobsters and other shellfish.

Like the zebra mussel, which bonds to boats and can clog pipes at sewage-treatment plants, the sea squirt is an invasive species that UConn researchers believe hitched a ride on an ocean-faring vessel from Asia and dropped into the Sound. There are about 3,000 known species of sea squirts. The one drawing attention here is known as didemnum.

It looks like a mass of rubbery goo and can attach to anything from marina pilings to ship hulls to the grainy, sandy bottom of the Sound.

“This thing has the potential for causing significant economic impact when it attaches to the floor of the Sound, where it blankets and suffocates shellfish and lobsters,” said Ivar Babb, director of UConn’s Undersea Research Center at Avery Point in Groton. “They have no known predators. Their surfaces have a pH level of 2, which makes them quite acidic. Nothing grows on it.”

Sea squirts, depending on the species, range in color from a creamy translucent pearl to olive or tan. In Japan, there are some red species.

They reproduce quickly and form large mats covering an ocean floor. And breaking them apart seems to do no good, Babb said, because, like sea stars that become damaged, they can grow replacement parts. In other words, splitting one sea squirt in half doesn’t kill it — it only creates two of the plankton-eating creatures.

“It looks like a blob. It doesn’t have that graceful look that a jellyfish has floating carefree on the surface of the water,” Babb said. “This thing is ugly. It has no socially redeeming virtues.”

What concerns UConn and the aquaculture industry is the sea squirt’s incredible ability to reproduce and form large ocean-floor mats that suffocate other sea life. The UConn researchers want to document how much of the Sound’s floor the sea squirt blankets.

….

“We are seeing come large colonies of these sea squirts,” said Robert Whitlach, a professor of marine sciences at UConn at Avery Point, on board the boat Tuesday afternoon. “Sometimes they are a few inches in diameter; other times they are a mat 4 to 5 square feet. What’s surprising is that we didn’t find them in the area that we originally expected to. We’re finding them where we are now, 1 miles south of Stonington, near the Rhode Island/Connecticut border.” If the scientists don’t find bigger quantities of the blob-like creature, they may use chlorine or vinegar to kill it. But first they’ll study what effect those substances might have on other marine life native to the Sound.

Sea squirt sightings are becoming more common in the United States, showing up in places as far flung as Puget Sound in Washington state to San Francisco and off Massachusetts and Maine.

….

Mosquito Immune System: Same Immune Factors Used To Fight Malaria Parasite And Infectious Pathogens

Mosquito Immune System: Same Immune Factors Used To Fight Malaria Parasite And Infectious Pathogens

Mosquitoes employ the same immune factors to fight off bacterial pathogens as they do to kill malaria-causing Plasmodium parasites, according to a study by researchers at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. The study identified several genes that encode proteins of the mosquito’s immune system.

All of the immune genes that were involved in limiting infection by the malaria parasites were also important for the resistance to bacterial infection. However, several immune genes that were essential for resistance to bacterial infection did not affect Plasmodium infection. According to the authors, the findings add to the understanding of mosquito immunity, and could contribute towards the development of malaria-control strategies based on blocking the parasite in the mosquito. The study is published in the June 8, 2006, edition of PloS Pathogens.

“Mosquitoes that transmit malaria can kill large portions of Plasmodium parasites, and some mosquito strains are totally resistant to Plasmodium. However, our observations suggest that mosquitoes have not evolved a highly-specific defense against malaria parasites. Instead, they employ factors of their antimicrobial defense system to combat the Plasmodium parasite,” said George Dimopoulos, Ph.D., senior author of the study and assistant professor with the Bloomberg School’s Malaria Research Institute. “The degree of mosquito susceptibility to Plasmodium, and thereby its capacity to transmit malaria, may therefore partly depend on the mosquito’s microbial exposure, which can differ greatly between different geographic sites. Potentially, we could boost the mosquito’s capacity to fight the malaria parasite by exposing it to certain microbes or compounds that resemble the microbe molecules responsible for immune activation.”

In this study, the investigators also analyzed the immune responses of Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes to infection with different Plasmodium parasite species, one that causes malaria in humans and another that only infects rodents. The study revealed that mosquitoes mostly employ the same immune factors in defending against the two different Plasmodium species. Only a few immune genes were more important in the defense against either one of the two species.

“The mosquito’s immune system appears to employ a variety of antimicrobial defense factors (genes) against the malaria parasite, and can therefore significantly limit infection. The parasite, on the other hand, is capable of evading these defenses to a degree that allows its transmission by the mosquito. Now we have to figure out how to make the mosquito’s immune system more effective in killing malaria parasites at multiple stages that would render the development of evasive mechanisms impossible for the parasite,” said Dimopoulos.

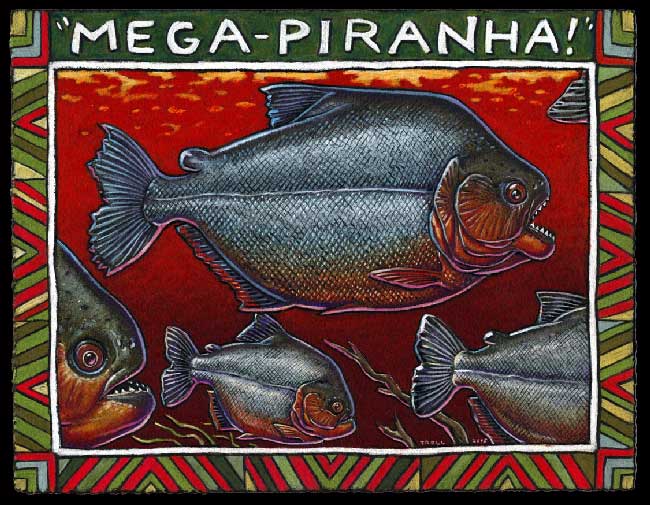

Megapiranha is the "meg"-est piranha of them all!

Toothy 3-foot Piranha Fossil Found

If you thought piranhas were scary, be glad Megapiranha is no longer around.

Megapiranha was up to 3 feet long (1 meter) – a fish-beast four times as big as piranhas living today, studies of its jawbones indicate. It lived about 8 million to 10 million years ago and might have been quite comfortable stalking cartoon animals in an “Ice Age” movie.

….

Now a newly uncovered jawbone of a transition species ties all these teeth together. Named Megapiranha paranensis, this previously unknown fossil fish bridges the evolutionary gap between flesh-eating piranhas and their plant-eating cousins.Here’s what’s known:

Present-day piranhas have a single row of triangular teeth, like the blade on a saw, explained the researchers. Pacu have two rows of square teeth, presumably for crushing fruits and seeds.

“In modern piranhas the teeth are arranged in a single file,” said Wasila Dahdul, a visiting scientist at the National Evolutionary Synthesis Center in North Carolina. “But in the relatives of piranhas – which tend to be herbivorous fishes – the teeth are in two rows.”

The new fossil shows an intermediate pattern: teeth in a zig-zag row. This suggests that the two rows in pacu were compressed to form a single row in piranhas. “It almost looks like the teeth are migrating from the second row into the first row,” said John Lundberg, curator at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia and a co-author of a study of the jawbone.

Bionic Turtle Army ready to kill

Allison, a rescued green sea turtle who has only one flipper, swims with the aid of a fin attached with neoprene at the Sea Turtle, Inc., in South Padre Island, Texas, Wednesday, April 8, 2009. Without the fin, developed at the turtle rescue facility, Allison can only swim in circles. The group had previously experimented with prosthetic flippers without luck.

One of my giant mutated turtles was spotted long ago:

Scientific American, 48:292,1883.

Captain Augustus G. Hall and the crew of the schooner Annie L. Hall vouch for the following:

On March 30, while on the Grand Bank, in latitude 40 10′, longitude 33, they discovered an immense live trunk turtle, which was at first thought to be a vessel bottom up. The schooner passed within twenty-five feet of the monster, and those on board had ample oppurtunity to estimate its dimensions by a comparison with the length of the schooner. The turtle was at least 40 feet long, 30 feet wide, and 30 feet from the apex of the back to the bottom of the under shell. The flippers were 20 feet long. It was not deemed advisable to attempt its capture.

EARS!!!!

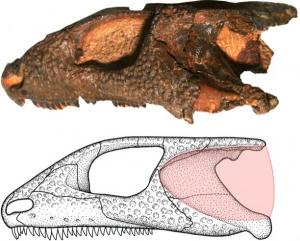

Prehistoric Reptiles From Russia Possessed The First Modern Ears

The discovery of the first anatomically modern ear in a group of 260 million-year-old fossil reptiles significantly pushes back the date of the origin of an advanced sense of hearing, and suggests the first known adaptations to living in the dark.

…..The ability of modern animals to hear a wide range of frequencies, highly important for prey capture, escape, and communication, was long assumed to have only evolved shortly before the origin of dinosaurs, not much longer than 200 million years ago, and therefore comparatively late in vertebrate history.

…..But why would these animals have possessed such an ear” “Of course this question cannot be answered with certainty”, explains Müller, “but when we compared these fossils with modern land vertebrates, we recognized that animals with an excellent sense of hearing such as cats, owls, or geckos, are all active at night or under low-light conditions.

Conjoined Nile Tilapia fish

Yahoo Link

Two conjoined Nile Tilapia fish, dubbed “Siamese Twin”, swim in a small aquarium in Bangkok October 3, 2008. They are both eight months old and share part of the skin together. The bigger fish tends to protect the smaller one from harm while the smaller one looks for food at the bottom of the aquarium.