The following article is unapologetically spoilerific on the subject of Prometheus. If you haven’t seen that film, I’d suggest doing that before reading this. Also, I should warn you that I am quite blunt about genital descriptions, in keeping with the imagery of the film.

Prometheus was one of the most hotly anticipated movies of the year. Fans of the Alien films, i.e: everyone, were chomping at the bit for the answers to the unanswerable questions posed by that film’s mysterious “Space Jockey”. Who was that guy? What was his connection to the titular alien? What happened to the rest of them? Well, Ridley Scott finally got his chance to try to answer all these questions in the form of Prometheus, a prequel of sorts to the 1979 film. We were finally going to find out what it was all about!

Well, not really. You see, Prometheus has loftier goals than that. Instead of explaining that one piece of scenery in Alien, this film treads new ground with an even more compelling question: What are humans all about? What’s the deal with existence? Well, let’s ask God. But, a lot of the fans weren’t too happy about that. They would argue that the film got off on the wrong foot right away by simply asking the wrong questions. But, you go with it in the hopes that the answers will be worth it and, of course, the answers provided are not the answers you want. This is the point at which Prometheus goes from the most hotly anticipated film of the year to one of the most divisive films of the decade.

Love it or hate it, Prometheus is what it is; golden-era science fiction through a modern lens. I think the divisive response comes from people either accepting that or rejecting it based on what they wanted. And that’s exactly the point of the film, as reinforced by its ending, to divide people by giving them answers that they don’t want. It’s the central plot conceit of the entire thing. Weyland (Guy Pearce) goes demanding gratification, Shaw (Noomi Rapace) has questions that only multiply as the film goes on and David (Michael Fassbender) has his own agenda to break free from his creator. Needless to say, none of them really get what they’re after.

In the end, Shaw and David leave together in search of more answers. David, the character who does not care about creation or answers and wants only to live is robbed of his ability to interact – throughout the film he is seen touching and operating everything he comes across – by being reduced to a disembodied head. Shaw, the ever-faithful true believer, wants to continue her quest for the ultimate creator. These two need each other in an odd sort of way. The response to the film was divided in much the same way. There were those who simply did not care for what Prometheus was exploring and so they rejected it and wanted to move on, but they are unable to fully interact with the film. Then there are those who want to look closer and closer for the answers. The film anticipated its own response. Even my own review was rather lukewarm and, to be perfectly honest, completely wrong. But, I belonged to the latter camp and a second viewing really nailed it for me, which is why I think it’s high time – especially with the blu ray and DVD out now – to give it a fair reassessment. In order to do that, we need to take a look at some of the specific elements.

Firstly: What Exactly is that Black Goo?

That black goo. It’s inconsistent, isn’t it? An Engineer drinks some at the start and it disintegrates him into his individual cells and reorganises his DNA, giving birth to all human life. Then, later, Charlie Holloway (Logan Marshall-Green drinks a tiny, miniscule drop of it and it mutates him on a cellular level into a colony of disgusting little creatures. When we see the weird tentacle emanating from Charlie’s eye, we get a good idea of how his cells are mutating. Much like the monsters in John Carpenter’s The Thing, every part of what he becomes is a whole. If Vickers (Charlize Theron) had not burned Charlie, he would probably have eventually become a wriggling mass of translucent worms. Even his semen is mutated, which we’ll get to later

The film begs the question of just how much do you need to strip a human down to his basic components before he stops resembling a human. The face we see in the vase chamber is described by David as “Remarkably human”, which is probably what the Engineer thinks when he looks at David in the third act. Weyland designed David to appear human so that other humans would be more comfortable working with him. Perhaps this is the reason we resemble the Engineers? Their design was dictated by the limitations of what they could relate to and, having moved beyond that into the hideous (to us) monsters that we see in the film, they are done with us.

When Fifield (Sean Harris) gets a face full of this stuff, it turns him into a contortionist zombie who kills a whole bunch of security personnel. Calling him a zombie is actually inaccurate, thematically speaking. I’ve seen him described as a werewolf too, what with his howling and his rising up from the surface of the moon on which the expedition takes place. In truth, his transformation reminds me of that of the character of Lucy Westenra from Bram Stoker’s “Dracula”. Awakened as a voracious and insatiable sexual predator after an initially unwanted sexual encounter. If you’ve never read Dracula, then it will benefit you to know that after the vampire Count’s arrival in England, he antagonises Lucy on a nightly basis until she eventually becomes a vampire with her own arcane appetites. Fifield, not obviously gay, gets lost with Millburn (Rafe Spall) and the pair share a symbolic sexual encounter. Millburn, throughout the film, has been pursuing Fifield as a sexual partner, which makes him Count Dracula in this instance (Rafe Spall once played Jonathan Harker in a BBC production of Dracula). Their encounter with a creature in the caves is loaded with fascinating imagery, but more on that later.

The black goo, then, is the entire concept of reproduction distilled and its physical reaction is not so much inconsistent as it is individual. It destroys the asexual Engineer (more on the Engineers’ asexuality later) to mutate his cells into new life, it turns Holloway into a vessel for mutated sperm and it changes Fifield into a sexual predator. The things it creates are entirely reproductive and I think that brings us neatly to the next major element of the film, one that should bring a lot of missing pieces into place.

The Monsters

There are three monsters in the film, not counting the mutated vampire Fifield. It would amuse me greatly to call them Genitalians, but we’ll stick with calling them Monsters. The first is a penis.

That is to say, it appear penile at first. It goes beyond phallic and into penile just by virtue of its appearance. However, it has a secret that it has in common with the second monster. The genital beast has a secret, it is not as gender specific as you might assume. As the penis monster opens a crest, it reveals a clear vagina.

This imagery of genitals with secrets is something that ties back to Freudian ideas. Specifically the case of “Little Hans” who, by Freud’s accounts, was obsessed with his mother’s genitalia and believed that her vagina (of which he knew nothing) held a secret penis and had the power to castrate, penetrate and envelop all at once. This creature, known as the Hammerpede (or the Vaginapenis as I like to call it), in revealing its sexually ambiguous genital secret, speaks to us of deep-seated fears. The fear of the misunderstanding of the genitalia of the opposite sex or even the genitalia of other members of our own sex. In calling the genitals the “privates” or “private parts” we have excluded them from society and so a true understanding of them is lost to naiveté, even as sexually active adults. We have neuroses about the size and shape of our genitalia and we experience a nervousness in revealing them to potential sexual partners. And so these fears come to rise. What secrets lurk within these perfectly ordinary genitals? None at all. But, the fear itself is embodied in these monsters. These genitals with secrets, a penis that opens out to reveal a vagina that envelops…

…ejaculates…

…gives birth…

…and finally penetrates…

Now, let’s take a look at that ejaculation imagery. While Millburn is very obviously gay, Fifield is most definitely a closet case and so this encounter that ends with him receiving a bucket-load of white ejaculate in the face could be said to be a turning point in his life. Perhaps he has never acted on his homosexuals desires before (a tragedy for a homosexual man of his age) and so it is this sexual awakening, along with the loss of Millburn, that leads to his change into the voracious sexual predator who attacks the all-male security staff of the Prometheus. The plot explanation is that Fifield acidic facial melts his helmet and he falls face-first into the black goo. Considering the black goo is the raw power of reproduction, imagine its effect on a suddenly awakened and extremely frustrated homosexual man in his late thirties. The result is anger and a new-found sexual appetite that he enforces on the men he encounters, just like Lucy Westenra.

Then we have our second monster which, for the sake of consistency, we will call the Penisvagina. The reasons for this should be obvious, especially if you have any familiarity with the Little Hans case mentioned above or with the Vagina Dentata idea. In this case, the creature is known officially as the Trilobite and its designer describes it as “celebration of the vulva”. Let’s get a look at this thing.

Now, in order to understand this creature we need to look at how it came into being, which is from one of Charlie’s mutated sperms.

The creature then grows in Shaw’s womb at an alarming rate and she is forced to improvise a caesarian section in order to save her own life. The infant is immediately hostile towards her as she rips out the umbilical chord and makes her escape from the medical pod. It’s this kind of unique imagery that Prometheus deals in that makes it so great.

This birthing scene, as over-the-top as it is, highlights something that David says later: “Doesn’t everyone want to see their parents dead?” Which, of course, Shaw and even Vickers will disagree with.

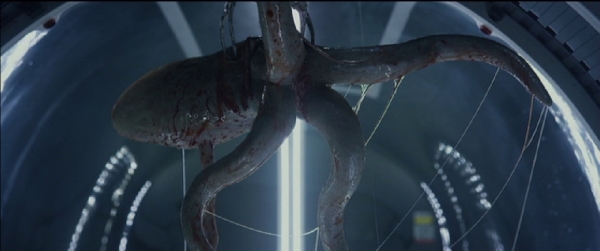

Later, Shaw is forced to return to the room in which the now-adult Penisvagina has been hiding. It has grown to an enormous size in her absence and in a last-ditch effort to survive an attack from an extremely grouchy Engineer, she sets it loose. We now see the full horror of its genital secrets.

As the labial openings peel back and the powerful tentacles pull the engineer toward it, the Penisvagina reveals its secret. Much like the Vaginapenis we saw earlier, it is hiding something that defies gender-specific sexuality.

Of course! A secret penis. And so the Penisvagina proves itself to be a creature capable of sexual aggression, castration, penetration…

…envelopment…

…and finally impregnation…

You’ll note that all of the penetration imagery in this film is oral. Obviously this is much more censor-friendly, but it also speaks of the more frightening idea that these creatures reproduce asexually and require only a vessel to impregnate with the fully formed infant that will ultimately destroy said vessel.

The Deacon, as it is officially known, is our third monster. This is the next logical progression from how the black goo evolves our physical beings. From the asexual Engineers, to the gender-specific sexual humans, to the gender-nonspecific hypersexual monsters, to the gender-specific hypersexual monster of the Deacon.

The Deacon is pure phallic force, penetration and destruction. By distilling it down like this, you can see how the gender-specific hypsersexual creature is potentially the most dangerous (especially if you’ve seen Alien, where the titular creature is almost exactly that). Ridley Scott says he “may or may not” use the Deacon for the sequel. Either way, I’m sure he’ll take this theme of sexual evolution to its next logical step.

The final element is one we currently need to scrape up from the floor of Vickers’ lifeboat.

The Engineers

We meet the Engineers in the film’s prologue as one of them sacrifices himself by drinking the black goo, which destroys and then rebuilds him on a genetic level. This is the foundation of the Engineers’ views on the creation of life. Sacrifice in the name of creation, or as David puts it: “Sometimes, in order to create, one must first destroy.” David, you see, understands the Engineers’ motives. He may even agree with them, but Weyland created him and thinks he deserves immortality for it. Naturally, when he tells this to the grouchy Engineer at the end (played by Welsh giant Ian Whyte, our generation’s Boris Karloff) he is met with contempt.

The Engineer, pissed off at being woken up by a bunch of humans, reminds me of Douglas Urbanski in The Social Network: “I have students in my office! Students!” Why is a robot talking to me? Why does this man think he deserves immortality for creating it? Doesn’t he know the sacrifice involved? I’ll show him! And so he wordlessly rips off David’s head and beats Weyland to death with it. Weyland dies, but David does not.

One thing which pops up repeatedly is the question of whether David has a soul. Weyland clearly states that he does not, but David probably believes on some level that he does. He claims to not experience emotions, but he appears to. He certainly has desires and interests and understands a thematic element from Laurence of Arabia well enough. But, if he has a soul, then do the monsters? Weyland’s handwaving explanation that David has no soul comes from the knowledge that he created him, so do the Engineers think the same of us? Quite possibly.

And what of Fifield’s pups; those robotic mapping probes that he not only created, but howls to affectionately and ultimately gets lost in spite of? Are they really any different to David? David finds one whimpering at an unopened door, suggesting some level of kinship such as that between a man and an animal. Fifield clearly has some fondness for them (he is apparently extremely lonely, probably on account of his being a closeted homosexual), but does he consider them to be creatures with souls?

Or Vickers; Weyland’s unwanted daughter? Is she any different to the creature that Shaw has removed from her? Does Vickers have any more right to life than the Penisvagina? Or David, for that matter? What does her relationship with Captain Janek (Idris Elba) mean to her and why is he so willing to sacrifice himself? Perhaps he sees where the Engineers are coming from on this one. You need sacrifice if you want life to go on at all.

So, who are Shaw and David still searching for in the end? God. I said earlier that these two characters represent the two divided parties of the audience, but they really overlap so much. David is shown engaging with cinema and applying theoretical concepts he sees there into his work. As he recites the line “The trick, William Potter, is not minding that it hurts,” we perhaps get a glimpse into a more human character here than the real humans would ever give him credit for. He appears to have emotions, but claims not to; perhaps he is even more emotional than we are and he simply has to tell himself to not mind?

These are all interesting questions that make up Prometheus‘ rich tapestry. I said in my review upon the film’s release that it was not as good as Alien by quite a long way. Having reassessed it, I’m beginning to think it may actually be better than Alien. Examining the elements like this validates a quote by Ridley Scott on the film’s commentary, which I borrowed for the title of this piece: “They look like they make sense, don’t they?” Regardless of if you think it’s the best Ridley Scott film, it is undeniably the most Ridley Scott film. It perfectly encapsulates his instinctive storytelling style and distills his beliefs and ideas into a single cinematic movement and serves as perfect insight into the Freudian nightmare that is his brain. Time will be kind to this film, just as it was to Alien.

Reading your article made me see the penisvagina as mirroring Vickers – the Freudian concept that a female left to grow up without a mother develops her own figurative penis and seeks to castrate, dominate, and control males. Except this is the idea physically manifested. As a penisvagina-monster.

I thought the sexuality of Millburn and Fifield were more ambiguous, and less of a sexual awakening and instead sexual confusion. After the homoerotic encounter Fifield comes back as this sort of confused raging creature. Doesn’t the captain ask “What the hell is that?” Fifield can’t speak or he would be asking “What am I?” in regards to his own sexuality.

Regardless, interesting article and viewpoints.

I think the confusion is dealt with during the attack itself: “I don’t want to touch it!” “Touch it, man!” Reading Fifield’s change as being a manifestation of confusion, rather than realisation is equally valid and I can’t really argue against it.

I don’t think fifield and milburn are homosexuals like you suggest. It think they just represent the extremes of human curiosity – the ego and super ego. Milburn is too curious and confident in his scientific abilities and is killed by the subject of his study (not unlike steve Irwin or the grizzly man Timothy treadwell) Fifield on the other hand is antisocial and is afraid of other people and just wants to study rocks and use robotic probes to explore the world – staying safe like the superego without any risk. They both represent the beta male who is unwilling and unable to take a leadership role and make good decisions in June face of conflict… Which is why they die. Ripley was neither reckless or unwilling to take risk which is why she was such a successful hero that survived against all odds.